Scientists Discover How Remdesivir Works to Inhibit Coronavirus

The antiviral acts like a paper jam in a photocopier, preventing the virus from copying its genetic code and spreading through the body.

Remdesivir is the only antiviral drug approved for use in the U.S. against COVID-19. Photo courtesy of Gilead.

More effective antiviral treatments could be on the way after research from The University of Texas at Austin sheds new light on the COVID-19 antiviral drug remdesivir, the only treatment of its kind currently approved in the U.S. for the coronavirus.

The study is published today in the journal Molecular Cell.

Remdesivir targets a part of the coronavirus that allows it to make copies of itself and spread through the body. For the first time, scientists identified a critical mechanism that the drug uses and unearthed information that drug companies can use to develop new and improved antivirals to take advantage of the same trick.

According to co-author Kenneth Johnson, the finding could also lead to more potent drugs, meaning a patient could take less of a dose, see fewer side effects and experience faster relief.

"Right now, it's a five-day regimen of taking quite a bit of remdesivir," said Johnson, professor of molecular biosciences at UT Austin. "That's inconvenient and comes with side effects. What if you could take just one pill and that was all you needed to do? That would make a huge difference in terms of the here and now."

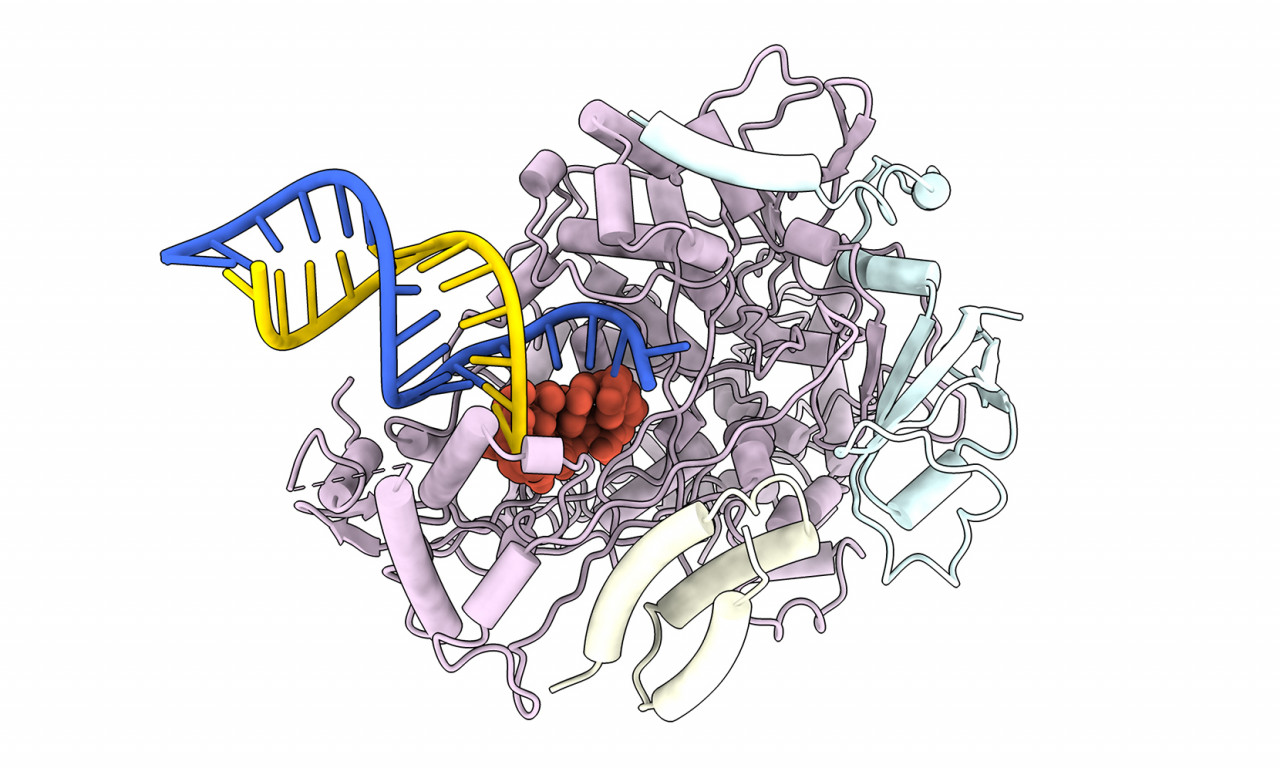

Study co-author David Taylor likens the trick the team identified to a paper jam in the virus's photocopier. Remdesivir shuts down this photocopier — called an RNA polymerase — by preventing copying of the virus's genetic code and its ability to churn out duplicates and spread through the body. The team detected where the drug manages to gum up the gears, grinding the machine to a halt.

"We were able to identify the point where that paper jam happens," said Taylor, an assistant professor of molecular biosciences. "We know now exactly what's creating this block. So, if we want to make the blockage even worse, we could do so."

The search for more potent antivirals could soon become more urgent as new strains of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, regularly emerge.

"We might need other drugs that are like remdesivir, but different enough that they can then go after the mutated forms," Johnson said. "It's like having a backup system, like having an emergency parachute in case the main chute doesn't work."

The study's co-first authors are postdoctoral researcher Jack Bravo and graduate student Tyler Dangerfield.

The team re-created in a lab dish the process that plays out in a patient who is infected with SARS-CoV-2 and then receives remdesivir. In a scientific first, the scientists developed a method for producing fully functional RNA polymerases to copy the viral genetic material. Next, they added a form of remdesivir. As the drug did its work, the researchers paused the process just after the reaction with remdesivir was completed (15-20 seconds) and took a 3D snapshot of the molecules in exquisite detail using a cryo-electron microscope in UT Austin's Sauer Structural Biology Laboratory. The image allowed them to reconstruct exactly how remdesivir gums up the copying process.

Johnson said that SARS-CoV-2 is the third coronavirus to make the leap from animals to humans in less than 20 years. So even if this pandemic is brought under control soon, it still makes sense to continue developing weapons against coronaviruses.

"This is not the last unique coronavirus that's going to come after us," Johnson said. "Having better antivirals could buy us time to develop vaccines against potential future outbreaks."

The version of the paper published today is a pre-proof, meaning that it has been accepted for publication and peer reviewed, but has yet to be fully formatted for final publication. It is currently slated to appear in a print edition of the journal in April.

This work was supported in part by the Welch Foundation, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH, Army Research Office, and the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation. David Taylor is a CPRIT scholar supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas and an Army Young Investigator supported by the Army Research Office.

Remdesivir molecules (red) block the copying of an original strand of RNA (blue) into a new copy (yellow) by the coronavirus’ RNA polymerase. Credit: University of Texas at Austin.